By the time she was 16,400-feet high in the Himalayas, Elise Wortley had learned to deal with altitude sickness and blistered feet. She’d even gotten used to her uncomfortable leather boots slipping on the rocks as she picked her way between sheets of ice and tufts of coarse grass. But as the sun went down near Kangchenjunga basecamp—the third highest peak in the world—it was the extreme, bone-chilling temperature that nearly broke her.

“I’ll never forget that night,” says the 29-year-old Londoner. “It was -15 degrees Celsius and I had ice in my hair and all over my blanket. The ground was too wet to make a fire. I remember thinking, ‘I’m going to die.’”

Nowadays, trekkers in Thangu Valley are equipped with snow-proof tents and buttoned up in state-of-the-art clothing to protect them from the harsh conditions that characterize that strip of northern India. Not so for Wortley. In 2017, she embarked on a journey that she’d been dreaming of since age 16, when she read a book that changed her life: My Journey to Lhasa by Alexandra David-Néel. Published in 1927, the autobiography charts the French female explorer’s 14-year expedition to Tibet, between 1911 and 1925. She traveled overland across Europe before finally reaching the town of Lachen in Sikkim, a northern region of India that juts out between Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan. Making the region her home for four years, it was from there that she first caught a glimpse of Tibet and vowed to enter it, eventually making it over the border by disguising herself as a beggar. Entry was forbidden for foreigners at the time, and it was unthinkable for a solo European woman to embark on such a journey alone.

“Women just didn’t do things like that,” Wortley says. “When I was a teenager I was shy and I dealt with extreme anxiety for years. The fact that she’d done this epic voyage fascinated me. I always had this inkling that maybe I could follow in her footsteps, but at the time, I was so anxious, I struggled to get on the bus.”

Part self-funded and part-funded by travel company Exodus, for whom she was working at the time, Wortley set off for Sikkim in 2017. An avid traveler, both personally and professionally, it wasn’t her first trip to India (she had already traveled extensively in Southeast Asia, Senegal and South Africa), but it was certainly her most adventurous. Joined by camerawoman Emily Almond Barr and local female mountain guide Jangu, Wortley recreated a portion of David-Néel’s journey from regional capital Gangtok to Kangchenjunga on the Tibetan border, covering some 435 miles by foot in a month-long trek. Keen to recreate David-Néel’s experience to the full, she made a mad-cap pledge to only take with her the equipment available to the French explorer in the 1920s. She traded in all modern-day comforts (minus emergency medical supplies) for a yak wool coat, rubber-soled boots, and a wooden backpack that she’d fashioned from an old chair, some rope, and an Indian wicker basket that she bought from a market in Gangtok.

“I went the whole hog. I had 1920s underwear—a cotton bra and high-waisted pants, and a woolen undergarment that was so itchy,” Wortley says. “The ropes on my backpack rubbed a lot, I had scabs on my shoulders. But I had to know how it felt to do it that way. The journeys of female explorers were way more hardcore than for their male counterparts. It was much more dangerous [for them] and they had to deal with the physical elements but also their periods, and even having to hide the fact they were women.”

Despite the decades separating their adventures, it wasn’t just the old-school underwear that aligned Wortley’s experience with David-Néel’s. “The scenery that she describes so beautifully in the book hasn’t changed. Mountains don’t change, not in 100 years anyway,” she says. “And she writes about how any house she passed welcomed her in, as they do now. You have a Tibetan tea with salt and butter, you have a chat even though no one knows what anyone’s saying.”

Wortley and her small team had to stop short of Lhasa due to similar difficulties in entering Tibet today, but the experience inspired her to celebrate other female explorers of the past. She pledged to continue to undertake expeditions to other extreme terrains explored and catalogued by intrepid women, under the name Woman With Altitude, in 2017.

“There are so many women like this and they’re not household names, but they should be,” Wortley says. “Annie Smith Peck was the first person to climb the north peak of the Huascarán in Peru. Ursula Graham Bower left England for India and ended up marrying the chief of the Naga tribe. And no one knows about her! The only problem is that it’s hard to find much written about explorers that aren’t white and European. But I’ve found some warrior queens and Tibetan nuns that I’m looking into.”

While Wortley’s main aim is to celebrate the achievements of historical female explorers, there’s a charitable element to her expeditions, too. “Because the project is woman-based, I wanted to help women in the areas I’m going to in some way,” she says. As part of the Himalayan project, she raised £2,500 ($3,000) for the charity Freedom Kit Bags, which provides girls in rural Nepal with reusable bags of sanitary products.

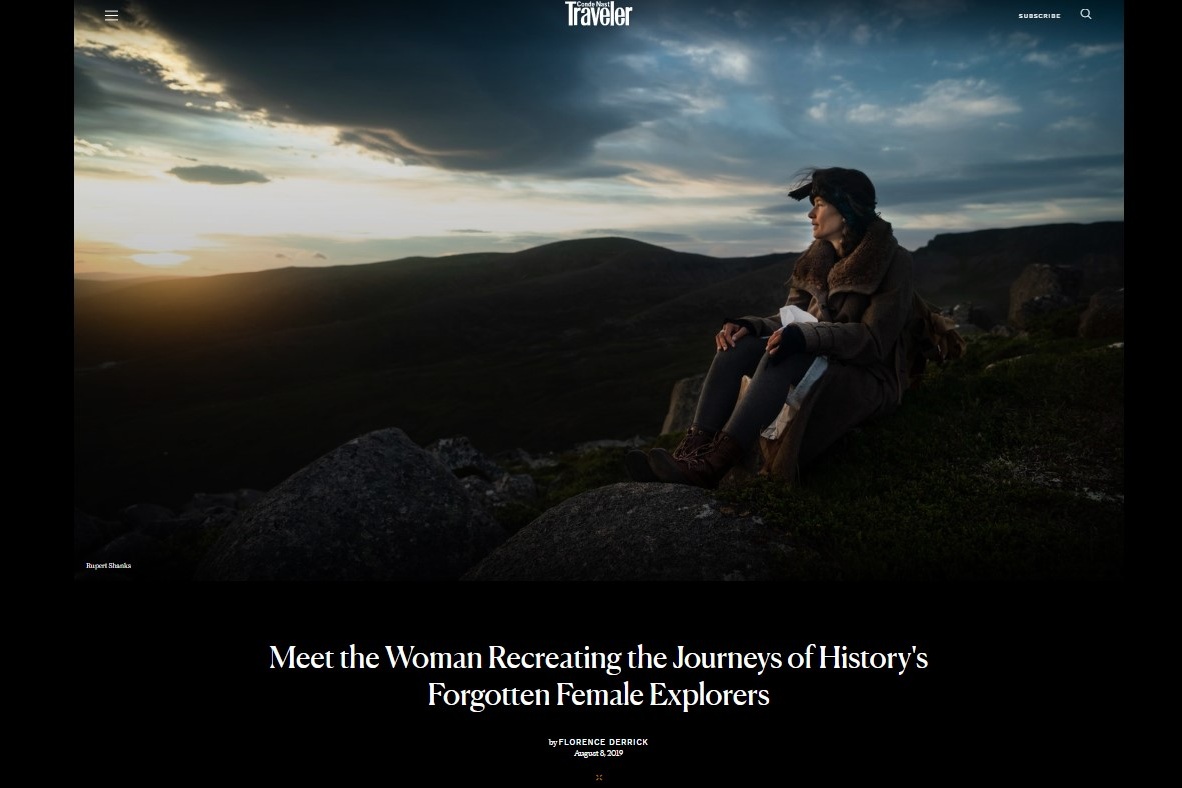

When we spoke, Wortley was preparing for her second trip (which she has since completed), following in the footsteps of Scottish explorer Nan Shepherd, who scaled the six highest peaks in the Cairngorm Mountains and catalogued it in her book The Living Mountain. Written in the 1940s but not published until 1977, it’s now considered a masterpiece of poetic non-fiction.

“It was written when people were racing to be the first people to scale peaks,” Wortley says. “She was into Taoism and saw it in the water, rocks, the sky, and the air. She wrote this about seeing the mountain as a whole.” Mostly alone, Wortley wandered between the peaks and lochs of the Cairngorm National Park for three weeks, equipped with a wartime gas cooker, a canvas tent, and old-school food supplies—mostly potatoes, cheese, and eggs. Part-sponsored by Wilderness Scotland, she was raising money for Scottish Women’s Aid and hopes to use these two projects to pitch a television series to fund forthcoming expeditions.

Wortley’s adventures are all the more impressive when you consider how alien the concept felt to her at the beginning. “Five years ago, my anxiety was so bad that I couldn’t even get on a bus,” she says. “But I could read Alexandra David-Néel and think, if she managed to leave Europe on her own and do this, I’m sure I can get on the Tube. I just want to make people more aware of these women, so they can inspire others.”