As the wooden shutters fold back, the dark restoration studio is flooded with Tuscan sunlight, illuminating an enormous canvas. Seven metres by two, it’s a 16th-century rendering of the Last Supper, a favoured theme for painters of the Renaissance. Versions of the scene are found in monasteries all over Florence – but this one has some unusual traits.

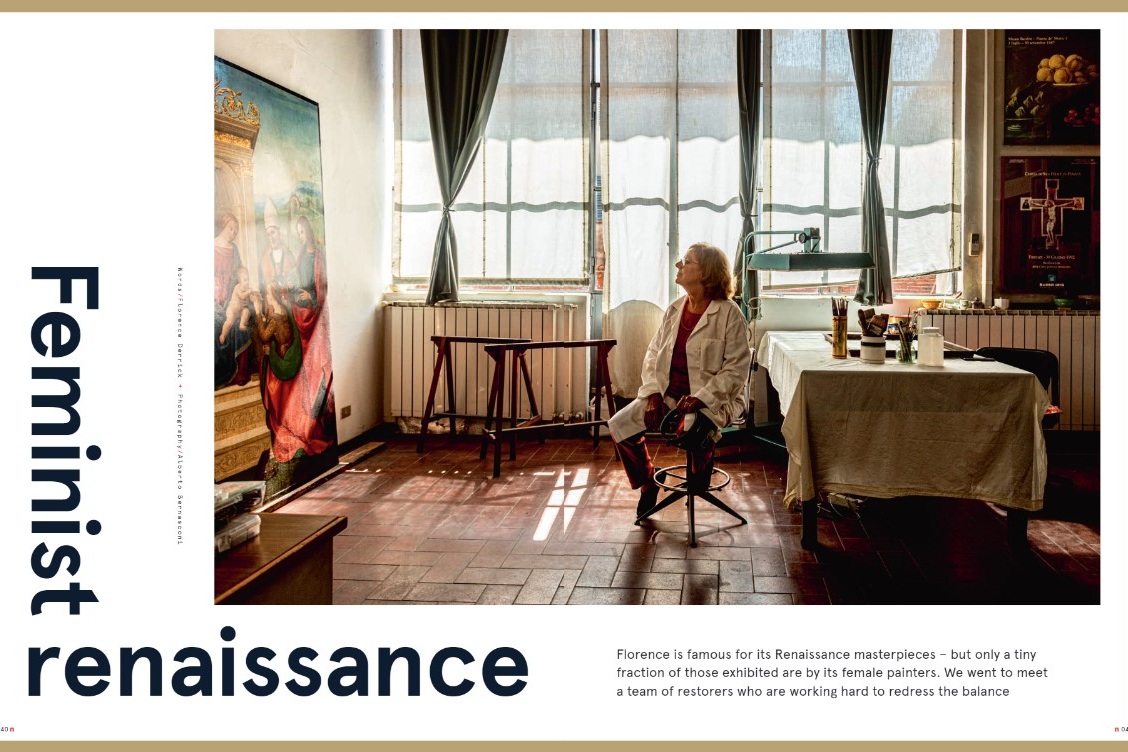

“There’s a wonderful attention to how the table is set,” says Rosella Lari, an art restorer who’s just completed four years on this work – etching away years of dirt and damage, and applying earth-tone paint and protective varnish. “It’s the only Last Supper I’m aware of that has an ironed tablecloth.”

As well as the cloth, with its perfectly pressed folds, the table is replete with chunky bread rolls, fava beans, roasted meat and salad; wine glasses are filled to the brim. It makes a down-to-earth contrast with other Last Suppers, which mostly display empty plates and glasses, and a distinct lack of actual eating. There’s a good reason for this, according to Lari. It was painted by a woman.

While many of us will be familiar with the big male names of Renaissance art who worked in Florence in the 1500s – da Vinci, Botticelli, Caravaggio – few will have heard of their female counterparts. Like self-taught artist and nun Plautilla Nelli, whose newly restored Last Supper is the largest known canvas by an early-modern female artist.

The painting’s crowdfunded restoration is the latest and most ambitious project from Advancing Women Artists (AWA) – a Florence-based non-profit organisation that searches for forgotten works by women artists, restores them, and supports galleries and museums in exhibiting them to the public. Since its launch in 2009 by the late American philanthropist Jane Fortune, AWA’s four-women-strong team has restored 65 works. There are now 124 by female artists on display in the city, but still a further 1,600 in storage – most of which are in dire need of restoration.

“When people come here, they want to see Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci,” says Linda Falcone, a former journalist and close friend of Fortune who now runs AWA and believes there’s just as much to gain from artworks by women. “They’re valuable from both an artistic and social point of view,” she says. “In some cases they’re the only social documents that testify to their lives.”

The organisation was born after Fortune came across a woodworm-infested oil painting by Nelli, Lamentation with Saints, in the San Marco Museum – and vowed to pay for its restoration herself. That led to a city-wide quest for the nun’s forgotten works, eventually found in Florence’s museum deposits, particularly the San Salvi monastery (now a museum).

It’s no coincidence that women’s art is often found in religious buildings, as much of it was produced in convents, which were unexpected centres of female creativity in 16th-century Italy. “To enter a convent like Nelli’s, families had to pay a dowry, and women of talent, who could paint or sing, could pay less because they were considered a resource,” explains Falcone. “People wanted to buy devotional art from nuns to feel closer to God.”

But while their talents were recognised – and some were commercially successful – a life of quiet chastity left little opportunity for nuns to study the human form, leaving them mainly with drawings from prominent male artists to work from. “They were painting things they had access to when they weren’t allowed to go to academies or paint nude models – so women’s portraits, and what they were preparing for dinner.”

It’s not known how many women artists were working in this period, but Giorgio Vasari, their contemporary and the world’s first art historian, mentions just four in his Lives of the Artists. There are complex obstacles to uncovering their works. “When we first approached galleries, they had no gender-based records of what they had,” reveals Falcone. She has personally sifted through countless museum archives to find art by women – a frustrating task, as the records are often handwritten, inconsistent and gender ambiguous, listing artists by initials rather than their full names.

This is, however, good news for today’s visitor who’s interested in knowing more, as they don’t have to do any digging. There’s now a Women Artists’ Trail, put together by the AWA, which is printed at the back of Invisible Women, Fortune’s book charting her hunt for forgotten women’s art. Following it, book in hand, is an easy way to see art by women while also taking in some of the city’s finest institutions.

One of the stops is San Salvi, which Falcone says has become known as “Nelli’s home… There are five of her works there now, four of which we restored and asked them to exhibit. Before, they were covered in pigeon droppings, they’d been gnawed by rats, someone had gone at the warping with a hammer.”

The revived paintings have a raw, emotional power that sets them apart from their more idealised counterparts by male artists. Nelli’s Lamentation puts the feminine experience in focus, her female characters’ eyes red-raw from crying as they cradle Christ’s lifeless body.

One of the trail’s other must-visit spots is the Palazzo Pitti – a vast Renaissance palace linked to the Uffizi by the arched Ponte Vecchio bridge, where the Pitti and Medici families (the world’s first modern bankers and the primary patrons of Renaissance art) lived between the 15th and 18th centuries. The setting alone is a visual overload, thanks to its deep-red walls, gilded cornices and chandeliers.

AWA runs an Invisible Women tour through the Palazzo Pitti with guiding company Freya’s Florence, that even goes into locked-off areas to view a set of 21 still lives by Giovanni Garzona – the most represented female artist in the gallery, although her work is not on public display. It’s also home to an unusual Baroque masterpiece: David and Bathsheba by Artemisia Gentileschi – the “poster child” of early modern female painting, according to Falcone. She and Fortune campaigned to have the work restored in 2008 after 363 years in storage.

A 10-minute walk north is another hidden work by Gentileschi at Casa Buonarroti – a mansion once owned by the artist Michelangelo. On a wood-panelled ceiling alongside 41 works by men, it’s a self-portrait under the guise of an Allegory of Inclination. Invoicing records show that she was paid three times more than her male counterparts for the work.

“Artemisia was a smart businesswoman and very successful,” says Falcone. “Because of the institutions’ focus on the male masters, people aren’t aware of that. We’re restoring more than paintings – we’re restoring these women’s identities.”

Nowhere is this more important than at the world-famous Uffizi, which houses the most works produced by women before the 19th century. In 2017, the gallery held its first Nelli exhibition, with free entry to women on International Women’s Day and a pledge to run an annual series on women’s art.

“We spent 10 years restoring 13 works by Nelli, which laid the groundwork for the Uffizi show,” Falcone explains. “Our attitude is collaborative and kudos to those who get the message, but there’s still a lot of art that’s not accessible to the public.”

There are still plenty of frustrations, too. “There are directors who ask why you’d want to restore art by women, and the general public wants to stay on the beaten track, which doesn’t yet include work by female artists. It’s about educating on the value of these works and understanding who your public is.”

It’s slow progress but early women’s art is becoming increasingly visible around the world. Visitors this month to the Prado, in Madrid, can see an exhibition on Renaissance artists Sofonisba Anguissola, a painter in the court of King Phillip II, and Lavinia Fontana, thought to be the first professional female artist. In London, the National Portrait Gallery’s Pre-Raphaelite Sisters reveals the hidden stories of those on both sides of the easel (until 26 January). Next year will also see the UK’s first Gentileschi show, at the National Gallery.

Eike Schmidt, the Uffizi’s director, has seen an exponential rise of interest in Gentileschi’s work, which appears on social media second only to Botticelli’s.

“She’s a kind of Quentin Tarantino of the past, which has become fashionable,” he says, referring to her violent portrayal of Judith Slaying Holofernes – which shows the artist herself taking a sword to the throat of her antagonist (and, as some like to think, the patriarchy).

The drama surrounding Gentileschi has somewhat overshadowed Nelli’s more contemplative work, but her Last Supper, which went on permanent display last month at the Santa Maria Novella Museum, should up her profile considerably. Nelli was clearly proud of the work, as she has, unusually, signed the art, in the top corner, followed by the words: “Pray for the paintress.”

“Artists didn’t sign their work at that time,” says Lari. “She’s saying, ‘Plautilla made this.’ She knows she’s worth something.”

This is even more poignant when you consider that Nelli sold small devotional paintings in order to fund the huge painting, with the sole intention of hanging it in the refectory, just as the men did in monasteries. “Women’s history is just not told,” says Falcone. “But restoring a painting is restoring a moment in history. Plautilla’s signature makes an appeal to the future – and we’re answering it.”

advancingwomenartists.org