Fatima sits down at a wooden loom at the mouth of the cave and gestures for me to kneel beside her. Handing me a ball of wool, dyed yellow with saffron, she nods in encouragement as I attempt the fiddly process of weaving the next layer of the rug she’s working on, pushing it down with a metal comb.

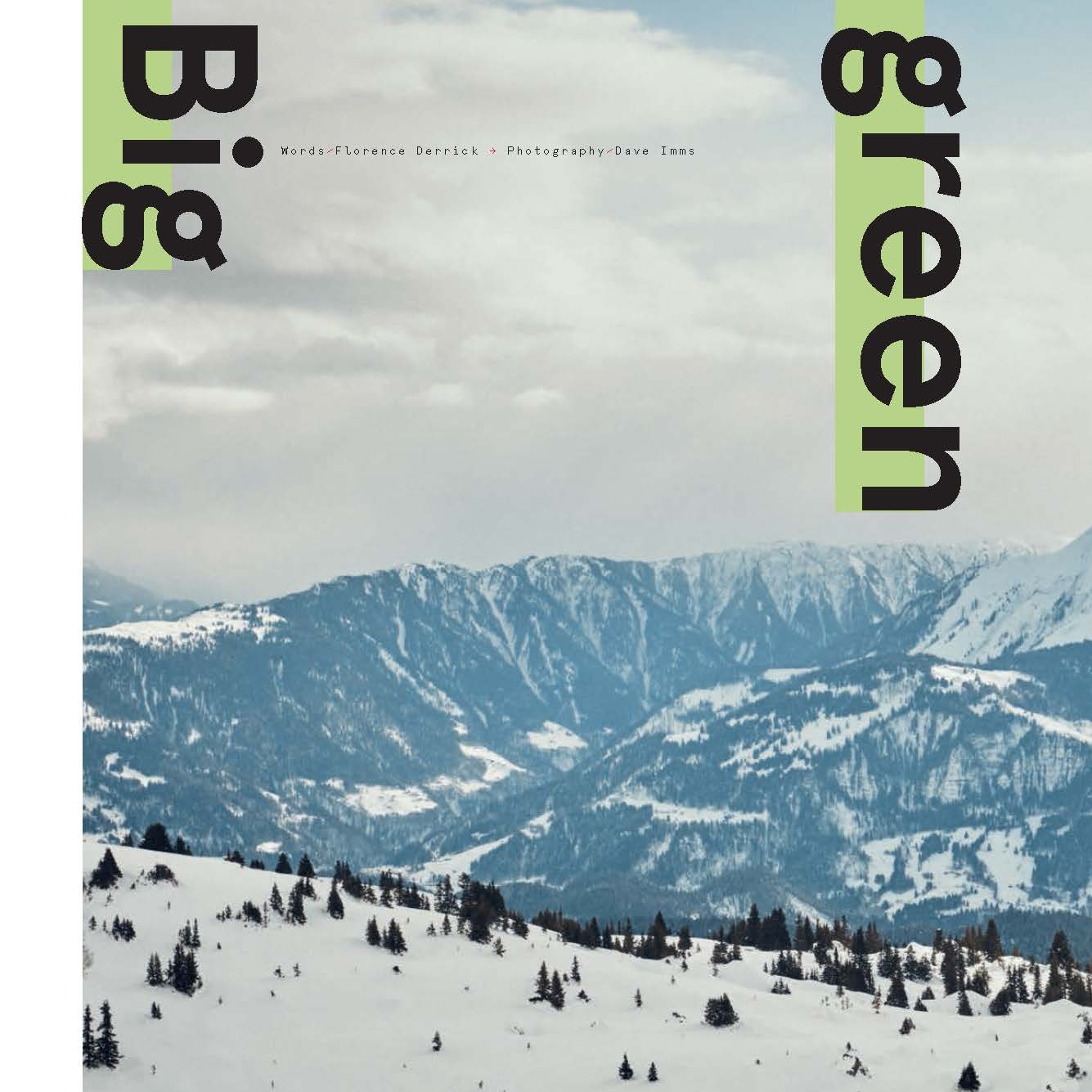

A nomadic Berber, Fatima lives in caves across the sparse, rocky plains of Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains with her family, herd of goats, chickens and mule. Making a small living through weaving and selling goat meat, she pursues a lifestyle that hasn’t changed for thousands of years – except that, two years ago, she began to supplement her family’s income by hosting tourists for a taste of nomad life.

“She says she weaves for just one hour each day, because it’s such intense work,” says my guide, Chama Ouammi, pouring steaming cups of mint tea. Ouammi acts as translator between visitors and the nomads, who only speak a regional Berber dialect. “I am Berber, too, so I understand this life,” she says.

We’re here for a taster of a Women’s Expedition in Morocco – the first female-only trek from tour operator Intrepid Travel. It takes groups of up to 12 women on an eight-day immersive journey through the country, staying at homestays in the Atlas Mountains. These trips are also organised and guided by women, and men are noticeably absent from our travels. If they were here, we wouldn’t be baking bread, trying our hand at weaving and sipping tea with Fatima and her children.

“With men present you wouldn’t be able to enter women’s homes and break that cultural barrier,” Zina Bencheikh, Intrepid Group’s regional director for Europe, Middle East and North Africa, explained to me prior to this trip. “A lot of customers want to do challenging stuff like a trek, without being judged by men or seen all sweaty, but the main thing they want is to enter the women’s world.”

Women-only travel is one of the fastest growing sectors in the global travel industry – and demand for trips like these has been growing. The number of solo female travellers soared from 59 million to 138 million between 2014 and 2017, according to the World Tourism Organization, and 84% of all solo trips are now made by women.

Intrepid isn’t the only group responding to these figures. American operator smarTours launched women-only itineraries in Egypt, Morocco and Colombia last year, while Condé Nast Traveler invited its online community, Women Who Travel, on group trips to Colombia, Mexico and Cuba. But what makes these journeys into the Atlas Mountains special is that they’re actively encouraging women’s employment in Morocco.

“Intrepid is very committed to gender equality. But in 2017 we had less than 20% of female tour guides globally and in Morocco, we had none,” explains Bencheikh. “It’s a conservative country. Women seen leading groups of men and women in different cities, spending nights out of the house, was problematic.”

When her company instructed its global outposts to double their number of female tour guides by 2020, Bencheikh – who grew up in Canada, France and the UK before returning to Marrakech in her twenties – decided she had to unpick the cultural barriers stopping women from applying. She lobbied Morocco’s Ministry of Tourism to issue 1,000 new tour-guide licences, and campaigned to raise awareness among local women, encouraging them to apply. “It’s prestigious and really well paid,” she says. “Why wouldn’t women want to do it?”

At the same time, she launched a campaign in the M’Goun valley, a popular trekking region of the High Atlas, for an itinerary run by women, for women. “We didn’t want to shock the culture – and this way, the men accepted it,” she says. “In fact, they loved it. Their wives and sisters bring in more income.”

Now around 100 Moroccan women have tour guide licences, and the Intrepid team has built a network of women-led suppliers and homestays that had been cut off from the benefits of tourism. We visit one of these on our first night in the M’Goun valley, after a six-hour winding drive from Marrakech, over the barren, snow-dusted Tichka summit and past the mud-built kasbah of Aït Benhaddou, where scenes in Gladiator and Game of Thrones have been filmed.

We pull up in Agouti, a hamlet of low-rise stone houses surrounded by almond and fig trees, and receive an open-armed welcome from a family of six women, dressed in full-length velvet dresses in purples, blues and greens. I spend the evening cross-legged on the concrete kitchen floor with our hostess Ajo Bendaoud, peeling vegetables for a tagine and making couscous from scratch, rolling flour with water and oil, and steaming it slowly. We eat together, scooping up the delicious, spiced mixture with our hands.

Bendaoud picks up a drum and the women break into song, encouraging me to clap and sing along, making up lyrics as I try to imitate their Berber dialect. Ouammi, who speaks six languages, is our smiley go-between, but for the most part we connect through hand gestures, smiles and hugs. There’s something comforting about being ushered around the house by mothers and grandmothers, finding your place by lending a hand in domestic tasks that don’t much vary between cultures. In a female space, it’s easier to feel like an added-on family member, trusted to have a toddler plonked on your lap or to laugh your way through new dance moves without fear of looking silly.

The next morning, I embark on an early morning trek to visit the nomadic community with another local woman, Mama Bie. We stroll through lush orchards until we reach a craggy gorge, leap over rivers on stepping stones and pause to eat fresh tangerines while she tells me her story via Ouammi.

In rural Morocco, more than 80% of women are illiterate, and arranged marriage is common – at as young as 13 for girls – typically leading to a life of child-rearing and housework. Mama Bie, now in her late fifties, is one such woman. She divorced aged 17 and became a single mother to her young son – her legal right, but a socially precarious decision. “After my divorce I couldn’t trust anybody,” she says. “Society thinks you are a bad woman.”

Luckily, her brother supported her, and she’s worked at his hostel ever since. It was already in the Intrepid network but it wasn’t until the Women’s Expedition came along that Bie took on an active role with guests, leading treks and teaching them to make bread, with a female guide as mediator. “When I’m doing the expeditions, I’m not just thinking about housework,” she smiles.

Ouammi was raised in the next valley along. “There are ladies in Berber villages who are very smart, but can’t finish their studies because no one can support them,” she says. “I was lucky to have open-minded parents who encouraged me to follow my dreams.”

She studied computer management and went on to be a freelance tour guide in Marrakech, before Intrepid headhunted her for the Women’s Expedition. But being the youngest and first female tour guide from the M’Goun valley hasn’t come without obstacles. “My uncle is a tour guide and he said: ‘This job is too hard for you. You can’t carry heavy bags or trek up mountains, you’ll never marry in the future.’” But she didn’t listen to him. “Women can do everything men can, and more.”

After tea in the caves, we trek to the Gîte Tamaloute in Boutaghrar village, the hostel run by Bie and her brother Hussain. We reunite with some women from the night before, who greet us with all the excitement and affection of lifelong friends, before I’m whisked away and dressed up in regional celebration wear: a full-length toga-like dress, an elaborate headdress of pompoms and a back-combed fringe.

We parade outside and I’m thrown into a folkloric dance demonstration, learning the steps as my new friends spin me around to an increasingly frenzied drumbeat. Attempts to sit down are vetoed: we dance and laugh together for hours, unable to exchange words but finding a close bond nonetheless.

In rural Morocco, women lead private, domestic lives. Without the link set up by Bencheikh, and cultivated by guides like Ouammi, it would be near-impossible for women like Bie and Fatima to participate in the tourism industry – and for non-Moroccan women to communicate with them.

A business model like this gives an economic boost to women at every level of the supply chain, whether they are visible or not: from utilising the country’s only female-owned transport company to kick-starting careers for smart, ambitious would-be leaders, like Ouammi. Most striking of all, it leaves misconceptions by the wayside, opening the door to travel that creates real cross-cultural connections.

“With women, I can talk about anything, and they can, too,” says Ouammi. “We can share and learn from each other. My dream is to travel outside of Morocco and show the women who live in the mountains in Morocco, and the world, that Berber women can do anything.”

intrepidtravel.com