Nearly half (44 per cent) of women-owned businesses in the US are controlled by minority women, and across North America, indigenous entrepreneurship is on the up.

Last autumn, the Canadian government invested $2 billion in a new Women Entrepreneurship Strategy (WES) that seeks to double the number of women-owned businesses there by 2025, while funds to support indigenous women have never been more widely available.

But there’s an even more pressing reason to pay attention to the innovation of the world’s indigenous peoples: their territories are home to 80 per cent of the world’s biodiversity. As we fight a global pandemic and face climate change, it’s more important than ever to learn from indigenous communities how to rebalance our relationship with the environment.

To mark the UN’s International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples (9 August), we meet three indigenous entrepreneurs making an impact in North America – on their chosen industries, and on their native communities.

Harvesting Native American flavour: Melinda Williamson, founder of Morning Light Kombucha (USA)

For big city dwellers, kombucha is as commonplace as smashed avocado on toast. The fermented, sparkling tea has been homebrewed globally for centuries but just recently became a hipster household name, as a healthy alternative to soda. In the USA, kombucha sales increased 12-fold between 2014 and 2017, when the industry was worth US$600,000.

But while shelves in LA, New York City and Portland, Oregon – which reportedly buys 78 times more kombucha than the rest of the country – were stacked with the stuff, that wasn’t the case in the tiny town of Hoyt, Kansas. Yet one woman there was in dire need of some fermented magic.

“I was diagnosed with an autoimmune illness about 10 years ago,” says Melinda Williamson, founder of Morning Light Kombucha. “I started looking at ways to heal with food, instead of being on a lot of medication. I learned about kombucha, but at that time I could only get one brand.”

Williamson – a single mother who had just moved back to her native Kansas from Oklahoma, with her daughter – vowed to make her own, launching Morning Light Kombucha in 2016. But it was part of a bigger plan: to start a company that would directly support her Native American community, part of the Potawatomi tribe.

“I knew I wanted my business to be focused on sustainability, to create those conversations in our community,” she says. “And I wanted to source locally and forage for ingredients.”

Producing small batches of kombucha of up to just 55 gallons, Williamson gathers wild berries and flowers from her tribe’s local reservation to create some 100 all-natural kombucha flavours, which are then sold at several Kansas locations in refillable bottles. “I go out with my family and harvest,” says Williamson. “If I’m harvesting flowers I’ll dry them, if it’s fruits then I’ll clean them and freeze them, locking in the nutrients until I’m ready to use them. I work with farmers and only harvest what I need – it’s important that I have a small footprint.”

Sustainability is a key driving force for Williamson, who recycles and composts nearly 100 per cent of Morning Light’s brewing waste. But the world’s only indigenous kombucha brand – recognised by the USDA as part of American Indian Foods – is drawing the attention of bigger brands at food shows, offering an opportunity to expand.

“My goal was always to offer something local, not to see my product on the shelf at the grocery store,” admits Williamson. “But I’m blown away by how many tribal businesses are interested in my product. I would love to create speciality lines that are specific to tribes, whether that’s with roasted blue corn, camomile, lavender or prickly pear.” In the meantime, she’s been launching a recyclable canned line of kombucha, and using proceeds to fund local youth basketball and trips to pipeline protests in North Dakota. However she decides to scale up, her Potawatomi heritage will be at the fore.

Upcycling sustainable threads: Amy Yeung, founder of Orenda Tribe (USA)

For many in the fashion industry, designing for brands like Puma and Reebok sounds like a dream come true. New Mexico-based fashion designer Amy Yeung spent the majority of her career travelling the world, working for its biggest activewear brands – but decided to drop her career as it reached its height.

“I was raising my daughter alone, and had a moment when I realised I couldn’t do this job and be a good mother,” she says. “I was trying to raise my kid to be a conscious citizen but my career in fast fashion was filling up landfills, just to create wealth for companies without any heart. I started working on sustainable, small-batch projects, doing production in downtown LA rather than in China, working with brands that were willing to slow down and do things differently. And I also started Orenda Tribe.”

Since 2015, Yeung’s fashion company has ‘soulfully upcycled and reimagined vintage clothing’ – a process close to her heart, as it’s a hobby she’s always shared with her daughter. “She’s grown up understanding that all things have a special energy and are to be cherished,” says Yeung. “My daughter was basically the creative director, as she did everything with me. If you scroll back on Instagram, she’s the model in all the photos. It was a love project for us.” That love radiates through the products they create: rainbow tie-dyed jeans; vintage dresses stitched in primary colours; earth-coloured bead necklaces strung with juniper seeds nibbled clean by insects.

But the advent of Orenda Tribe coincided with another love project for Yeung – the rediscovery of her Native American roots. Born into Navajo Nation but adopted out to a non-native family, Yeung reconnected with her birth mother in her 30s and started to gradually reintegrate into the tribe.

“It’s where I was always supposed to be, but it took me a long time to get home,” she says. “I’ve only been physically living on ancestral lands for a year. I’m like a toddler, learning the language, the protocol, our culture. It’s a road that I have ahead of me as long as I live.”

As she travels that road, Yeung invests her expertise and the success of Orenda Tribe in the local Navajo community, by selling the work of other indigenous designers via her platform and collaborating with local talent. “Our youth are so expansively creative,” she says. “There are so many young creatives amplifying indigenous voices. It gives me so much hope for the future.”

Photo Credit: Pierre Manning

Yeung’s optimism flies in the face of the devastating impact that COVID-19 has had on her community. Between March and July 2020, she repurposed her skills to produce 80,000 masks for frontline workers, from fabric donated by her former clients, like Nike and Patagonia, and fundraised for 47,000 food and supply kits for every child in Navajo Nation. But as the world reels from the pandemic, Yeung can see an opportunity for positive change.

“We’re going to see so many indigenous brands, designers and creatives thrive in this new situation,” she says. “People don’t want to go to malls or stores anymore. We’re buying things on our phones and having them brought to us, and designers can sell whatever they want on social media. And do you really want to buy from H&M when you could buy from a young designer on Navajo Nation? The way things used to be, all based on greed and wealth, is crumbling. We want to surround ourselves with things made with heart.”

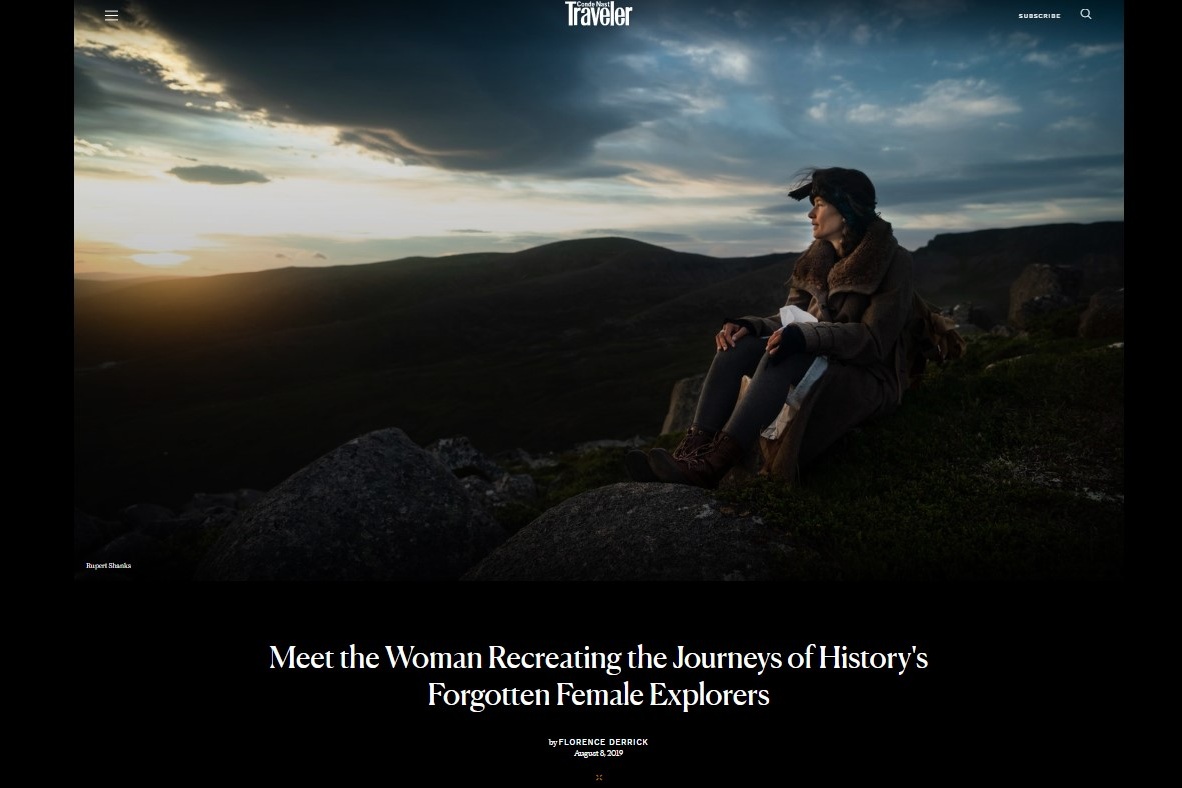

Flying high: Teara Fraser, founder & CEO of Iskwew Air (Canada)

When she was 30 years old, Teara Fraser spent her savings on going travelling for the first time. In Botswana, she sat in a small aircraft and felt her heart race as it swooped over the green swamps of the Okavango Delta. “The pilot was telling us the stories of the land, the trees, and the animals, and I thought – this guy has the coolest job ever,” says Fraser.

Two weeks later, she went skydiving. Almost 20 years later, Fraser can remember everything about that moment. “I can smell it, see it, tell you how I wanted to touch everything on the dashboard and know what it did,” she recalls. “I said to myself, I don’t care what it takes. I’m going to fly airplanes.”

It was easier said than done. As a single mother with two children, no post-secondary education and no knowledge about the aviation industry, Fraser had some odds stacked against her. But within a year, she had a commercial pilot’s license.

“Looking back, I don’t know how I did it,” she laughed. But it launched her career in aviation and gave her a business idea – to start a small aircraft service for indigenous tourism in her native Canada. “As a Métis woman, I want everything I do to be in service of community and indigenous peoples,” says Fraser. “And that’s something I can help with: connecting indigenous tourism partners and bringing travellers to more remote, smaller strips.”

The business didn’t take off for 10 years. Fraser eventually launched her airline in October 2019, naming it Iskwew Air (‘Iskwew’ means ‘woman’ in Cree language, nodding to her identity as an indigenous matriarch and as an antidote to the male-dominated aviation industry) and starting things off with a blessing ceremony at Vancouver International Airport, from the territory’s Musqueam tribe. But little did she know that an even greater challenge was around the corner.

“I like a challenge, but an airline startup during a global pandemic? Not ideal,” she says. “Pre-COVID, indigenous tourism was the fastest-growing aspect of tourism in Canada. People are looking for meaningful, authentic experiences that are connected to the people and the land. But it’s important that’s done in a really sustainable way, led by indigenous people, in communities that choose it for themselves.”

Iskwew Air has kept operational throughout the pandemic, transporting essential supplies and cargo to indigenous, remote communities. And Fraser is poised to pour her energy into indigenous tourism again once communities are ready to welcome visitors. When it’s safe, it won’t be a moment too soon.

“Indigenous people have so much wisdom that the world desperately needs,” says Fraser. “What’s beautiful is that the pandemic is connecting us in a collective experience worldwide. It gives us the opportunity to understand what’s possible, as indigenous peoples have done for time immemorial. This is an invitation from the world to do things differently and rebuild systems that are in better service to all people and the land.”