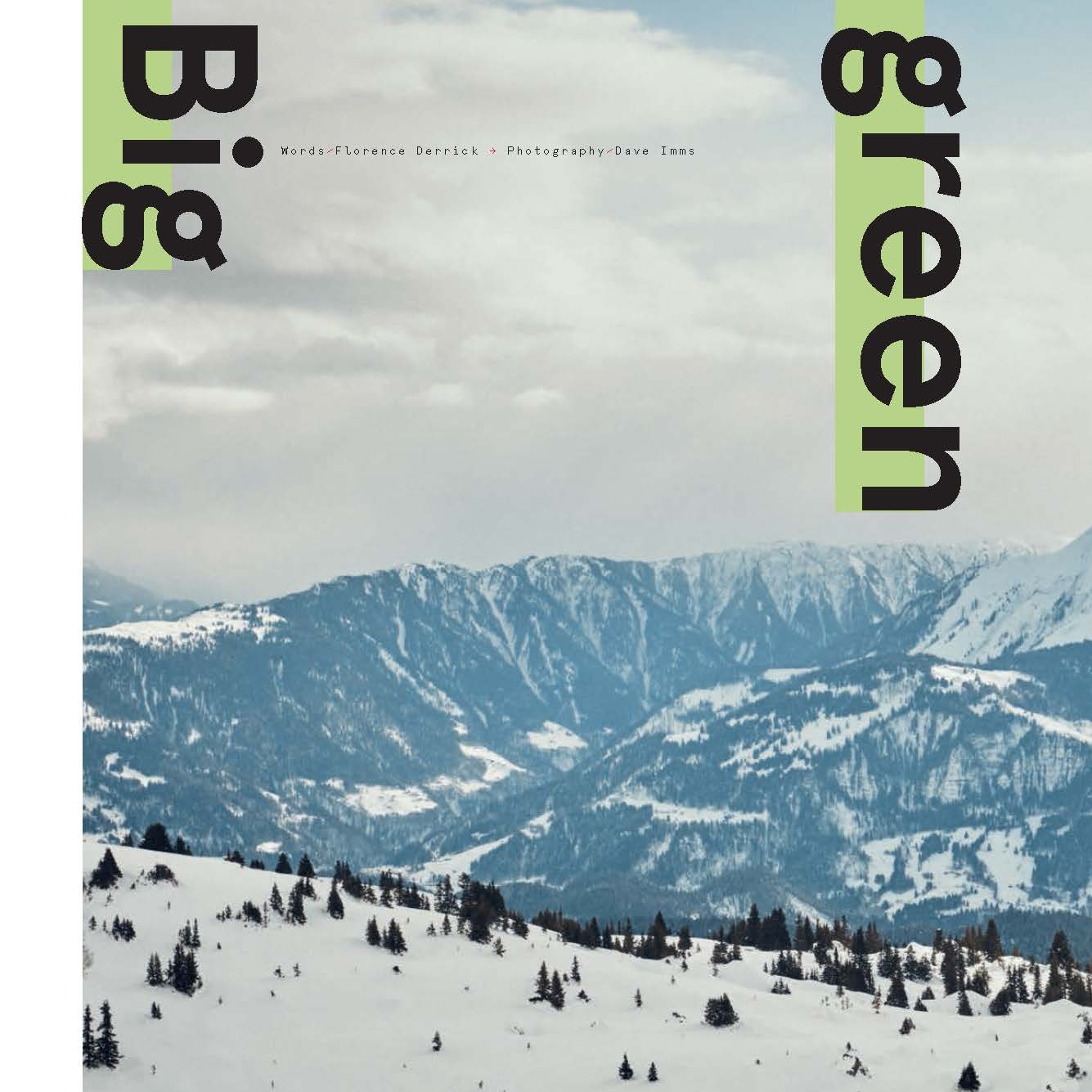

At daybreak, from the gondola station in the LAAX ski resort, the distant lights of snow groomers can just be made out through the fog. The vehicles crawl up the slopes on the last leg of their night shift, striving to finish before throngs of winter sports enthusiasts arrive, piling 80 at a time into the gondola cars at the first sign of sunlight.

There’ll be fresh powder for these early birds, thanks to the yellow snow cannons that line the newly smoothed runs. These blowers, which resemble giant hair dryers, have been topping up the natural snowfall overnight, fed with water from a nearby man-made lake.

At first glance, neither groomers nor cannons seem particularly eco-friendly, but they’re working together in a way that makes this Swiss mountain resort a world leader for green initiatives.

“The drivers have a GPS system that indicates exactly how much extra snow is needed where,” explains Reto Fry, environmental officer for the local area. Eco-friendly, high-tech machines like these can work together to enable more efficient use of resources: a key tenet of his sustainable vision for the resort.

Fry has become an expert in efficient use of resources since spearheading LAAX’s think-global, act-local sustainability concept, Greenstyle, which he’s run single-handedly since it launched in 2010. The resort was one of the first Alpine destinations to respond to the growing idea that mountain resorts might not be good for the environment.

Around 120 million people visit the Alps each year, and a big part of the draw is the proximity to the vast beauty of mountainous nature. Yet mass tourism – added to melting glaciers, rising snow lines and increasingly unpredictable snowfalls – threatens to harm the very environment that visitors seek to connect with.

Some suggest that skiing itself is too impactful and we should put down our ski poles for good but this is a drastic solution and one that would be devastating for Alpine communities. Mountain tourism has been the saviour of tiny, cut-off villages all over the Alps, particularly in Switzerland, where almost 170,000 citizens are directly employed by a tourism industry that generates CHF46.7 billion (US$46.7bn) annually.

Instead, the challenge today is for tourists to pick resorts with an eco-conscious approach – and for resorts to prioritise that approach. “The most important three topics for today’s generation are climate change, energy consumption and biodiversity,” Fry explains. “So I set out a solid framework for what we want to achieve.”

It’s not the first time that LAAX has attempted to project its ambitions ahead of the curve. The area was once marketed as part of the traditional and wealthy nearby town of Flims, but was rebranded, along with its 224km of slopes, under the banner of LAAX in 1997, reimagining itself as an extreme sports destination. It now has a world-renowned snowboarding freestyle and off-piste scene, is home to the world’s biggest halfpipe, and is attracting more youthful visitors each year thanks to its mountaintop co-working spaces and “urban slopestyle”. The modern resort has an average visitor age of 38 – significantly lower than the middle-aged average elsewhere in the Alps.

Greenstyle was the next logical step – a dedicated focus on sustainability that would chime with its eco-savvy clientele. It’s not just lip-service. Since 2010, the resort has run on 100% renewable electricity, mostly hydropower and solar (non-sustainable fuels are still used for heating). Last year its rocksresort hotel was recognised as the World’s Best Green Ski Hotel. It even produces a range of natty bags made from its recycled marketing pamphlets.

Fry is now ready to take it up a notch, recently proclaiming the plan to become carbon neutral and self-sufficient by 2030. To accomplish this feat, he’s divided his targets into seven focus areas: energy, zero waste, water, transportation, food and purchasing, biodiversity and communication. “Because of our renewable energy and energy efficiency strategy, I can now say that 100% renewable energy by 2023 in LAAX is totally possible,” he says. “We’re installing heating systems that run on biomass pellets and we’re planning to build a wind farm on a glacier.”

Fry’s food waste target feeds into the strategy, too. “We’ve set a goal to reduce residual waste by half, mainly through plastic recycling,” he explains. “We’re encouraging people to use reusable coffee cups and food waste is made into biogas.” As well as encouraging chefs to use local, seasonal and organic produce, the resort has invested in an automated food-waste management system called Kitro. In use at the Riders restaurant, a bin is fitted with a scale and a camera that photographs food waste each time more than 30g is deposited and sends reports back to the kitchen.

Other ongoing initiatives include providing electric-car charging stations and free bus shuttles; building roof gardens to create habitats for wild butterflies and bees; and recycling water so that mountain-fresh spring water is no longer used for sanitation as well as drinking – 7.5 million litres have already been saved since 2010 through new efficiency measures.

These ideas aren’t unique to LAAX: Chamonix has set its own target to reduce carbon emissions by 20% by 2020, while Villars, towards the Swiss border with France, has installed hybrid buses and solar panels. For Fry, it’s not about creating competition with other resorts but working together and taking inspiration from similar resorts’ initiatives. “I’m convinced that it’s possible to solve lots of our problems.”

Although he recognises there’s much work still to be done, he feels positive he can achieve his goals. “I have a family. I want to commit to their future. And the last year or two, I finally see the vision in my head coming together. Now, we just need to show others what we’re doing. We can’t influence everything but we can try to be a good example in the hope that others will join us on this path.” laax.com