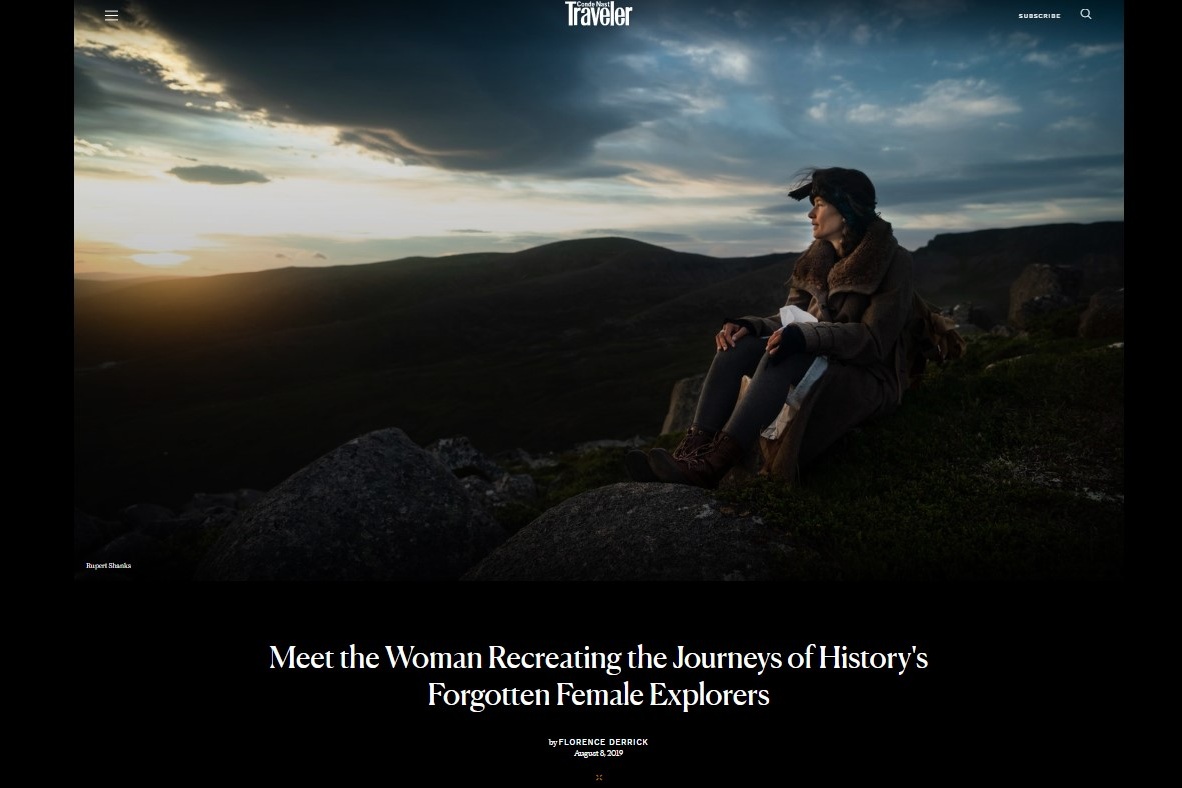

Did you know that at least 60% of the global tourism workforce is female, despite the fact that just 23% of board members in the industry are women? And there’s one corner of tourism where women are particularly underrepresented, especially when it comes to female tour guides: adventure travel.

According to adventure tour operator Untamed Borders, just 3% of accredited international mountain guides are women, and in countries where women’s educational opportunities and cultural expectations are limited, women are much more likely to take on lower-paid cleaning and clerical roles than guiding roles. These are the women that keep the world of travel turning – and are most likely to have been negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. But change is in the air.

The three following women, hailing from rural regions of Afghanistan, India and Morocco, represent the green shoots of a cultural shift towards women taking adventure tour guiding roles in global regions where this is unheard of. It’s partly down to the diversification work of companies such as Intrepid Travel, Responsible Travel, GAdventures and Untamed Borders, which are all committed to employing and training more female adventure travel guides.

The solo female travel trend has been growing in popularity in recent years, with Google Trends reporting a 131% rise in interest in 2019. Female-only tours from operators like Intrepid and SmarTours are providing more opportunities for female tour guides than ever before, some in conservative destinations such as Iran, Morocco, Nepal and Jordan, as well as experiences exclusively for women, for their guests. This could mean kohl beauty treatments in Jordan or trying on traditional wedding clothes in Morocco: the world of women that’s not accessible to men in those countries.

“Representation is a fundamental component of achieving equality and access to opportunities,” says Jenna Howieson, Inclusion and Diversity Lead at Skyscanner. “That’s why it’s so important to empower and celebrate the incredible women working in the tourism and tour guide industry. Through training and working as tour guides, women have access to financial autonomy and a well-respected job that connects them to the rest of the world. I hope that tour operators and those working in the travel industry will continue to connect with, amplify and empower even more female tour guides in the future.”

This International Women’s Day, let’s celebrate some of the women breaking the mould in the world of adventure guiding.

The first female guide in Morocco’s Aït Bouguemez valley: Chama

In the High Atlas Mountains, the serene Aït Bouguemez valley is home to many striking things: the towering summit of Morocco’s third-highest mountain, the M’Goun Massif; the rose-coloured, sleepy city of Azilal; indigenous Berber tribes; and a plucky young tour guide making it her mission to break down barriers wherever she goes.

“People say that women can’t do this job,” says Chama Ouammi. “They say it’s too hard for women to hike 20 kilometres, to carry heavy bags, to walk under the sun for more than four or five hours. Women are only to stay in the house, raising children, cleaning and cooking. But I’m opposed to that because women can do everything that men can do, there’s no difference between us. This is why I took the opportunity to go out of my village: to be a good example for ladies in Morocco and to challenge the obstacles of my society.”

Some of those obstacles were very close to home. After studying computer management, Chama began working as a freelance tour guide in Marrakesh before being headhunted by Intrepid Travel to be one of their first female tour guides on their Moroccan women’s expeditions. The company had lobbied Morocco’s Ministry of Tourism to issue some 100 new tour guide licenses to women, on passing a two-part licensing exam, which Chama benefitted from in 2018. But on qualifying, her uncle made it clear that tour guiding was not a path he approved of for his niece.

“My uncle said you can’t do this job, it’s only for men,” she says. “He said, if I had this job I wouldn’t be able to marry in the future, and people would judge me for travelling with different drivers and men. But he was jealous that I am the first female and youngest guide from my region.”

Luckily, Chama’s parents supported her ambitions and respected her wish to opt out of arranged marriage. It’s this support that not only has given Chama the confidence to boldly follow her career path, but has infused that path with such joy and grace. She’s aware of her good fortune: in rural Morocco, over 70% of women are illiterate and arranged marriage, as young as 13 or 14 for girls, is common, typically leading to a life of child-rearing and housework.

“My parents are very smart and always encouraged me to follow my dreams,” she says. “There are ladies in the Berber villages who are very clever, but they can’t finish their studies because no one can support them. I’m happy because I have good, open-minded parents.”

Now working as a freelance tour guide for several tour operators all over Morocco, including Intrepid, Chama gets the most out of the women-only tours that she guides. Speaking five languages and with a warmth that would make any visitor feel welcome, she embodies a kind of joyful, cross-cultural exchange that sometimes, in more conservative societies, is often only accessible between women.

“I really like working with just women because I can talk about anything, and they can too,” she says. “We can stay without headscarves. We can dance together, we can laugh together, in a way that you can’t do when men are there.

“It’s a very real cultural experience, from beginning to end. Some things are only for women.”

The first indigenous female tour guide from northern India: Jangu

India’s West Bengal state encompasses a dizzying range of landscapes, stretching from the tropical mangroves of the Bay of Bengal right up to the foothills of the Himalayas, passing tea fields and plantations along the way. It’s in these foothills that one woman has made history – by becoming the first woman in her indigenous Lepcha tribe to work as a mountain tour guide.

“This path came naturally to me, because I’ve been trekking since childhood and I have knowledge of this area,” says Jangu Lepcha. “I’m blessed to be surrounded by the Himalayas, rivers, forests and birds. All of this motivates me. I’ve wanted to do something like this since my childhood.”

Jangu’s main profession is developing and promoting homestays to tourists visiting her home village of Pedong and the surrounding area. She works as an ad hoc guide for guests travelling to the northern regions of West Bengal, responding to a gap she spotted in the market for a female, English-speaking guide. Capitalising on her lifelong love of nature, she first developed an interest in eco-tourism – and her business concept – while working on a tourism project in Siliguri (three hours’ drive south of Pedong).

“I realised that I could promote and conserve my own rich Lepcha culture through eco-tourism,” she says. “My father always instructed us in our culture and tradition, so I grew up very close to my indigenous culture. We have a unique way of living. The way we dress, our food identity, living habits, architecture.”

But working as a female tour guide was such a novel concept in her community, that Jangu set herself up as a self-employed guide and homestay consultant without even telling her family about her ambitions.

“I don’t know if they would have supported me initially, because I did it completely alone,” she says. “They knew I was into tourism but they didn’t know the passion I had. When I finally told them, they had different expectations – but now they understand and are proud of me.”

The Lepcha tribe, reliant on agriculture, river fishing and foraging medicinal plants from the region’s forests, had different expectations for Jangu, too. But her work has already made an impact on the community’s mindset.

“When I started working in tourism, my people didn’t know what a homestay was and were reluctant to have visitors,” she says. “But since I’ve helped them, homestays and tourism here are becoming very popular.”

It’s just as well, because Jangu is about to launch the project of her dreams: Miknaon, a wellness-oriented homestay in Pedong, due to open in October 2021.

“Being a Lepcha in this region, we own land from our ancestors,” she says. “I want to invite guests from all over the world, be their guide, let them come here to eat good food, do activities, yoga, hiking and be healthy. This is my future goal.”

Afghanistan’s first female tour guide: Fatima

You never know when inspiration might strike. When Fatima was eight years old, she was working as a shepherd – just like many children in the Lal wa Sarjangal district of Ghor province. This mountainous area in Hazarajat, central Afghanistan, relies primarily on agriculture, with families working the same land that Genghis Khan’s Mongol army grazed its horses on, in the early 13th century.

“It may be a little strange to many readers, but running on those high hills after animals was when I was first introduced to guiding and leading a group,” says Fatima (whose surname is omitted for safety reasons). “It was a tough experience, but guiding so many sheep and cows to find their food and enjoy life was a pleasure, too.”

But a long journey lay ahead before Fatima would lead her first group of tourists in Herat, Afghanistan’s third-largest city, for adventure tourism operator Untamed Borders in 2020. Age 23 now, she was lucky to receive an education as a child. Designated the least-developed country in the world by the UN, Afghanistan is a challenging place to grow up female: women’s employment opportunities and literacy rates are low, with 2.7 million girls out of school in 2018.

“My family permitted me to participate at a school whose roof was the scorching sun, seats were hot sand, and that most girls were strictly forbidden to attend,” Fatima remembers. “Luckily, I learned basic reading and writing.” It was this foundation that allowed her to continue her education, including English classes from charitable organisations, until it led her to undertaking a journalism and communications degree from Herat university. She caught the attention of Untamed Borders via her posts about Afghan history on a Facebook travel diary group, and led her first tour in 2020, despite the coronavirus pandemic disrupting trips to Herat.

Fatima’s two sisters followed a more traditional path. They were both married by age 15 and never learned to read or write. And when Fatima first told her parents her plans to become a tour guide, they were firmly against the idea. “I’ll never forget the eyes that looked at me strangely, the people that said, ‘you’re a girl and can’t do it’, or ‘it’s too dangerous’. But no one can stop me from doing what I love,” she says. “What is more beautiful than giving insights into the history, culture, food and traditions of my country?”

But as the first Afghan woman to do the job, no one was more aware of the difficulties ahead than Fatima.

“Before I started my career as a female guide, I often read tourism sites that would discourage women to travel in Afghanistan,” she says. “I asked myself, ‘if it’s dangerous to visit Afghanistan as a tourist woman, how is it possible to be a woman tour guide?’ This was very upsetting to me.

“Then I realised that I am the one who has to create this safe space. Tourist women are role models of courage and change. Women tourists matter, and as a woman tour guide, I matter too.”

In the future, Fatima aims to use her qualifications to work as a professional journalist as well as a guide, while uplifting women along the way. “My next plan is to establish a tourism organisation for empowering female tour guides,” she says. “I am the first female tour guide, but I don’t want to be the last. Afghanistan needs new guiding leaders with new perspectives, who have open minds and open hearts. This need is more crucial for Afghan women. I will do my best to be an agent of change and inspiration for individuals facing similar challenges that I faced as a tour guide and woman journalist.”